Traditional Andamanese life was not wretched or miserable, but neither was it paradise or idyll. The hostility shown towards strangers and other intruders was reflected in violence between and within local groups. Among the excitable males with their somewhat over-developed amour propre, violence in response to real or imagined insults was widespread. It took leaders of strong character to cool down the hotheads and to keep a check on the quarrels that could flare up at any time.

Only a minority of disputes escalated into violence, of course most ended in sulks of dignified silence, soon patched up or quietly forgotten. The presence and peace-making talents of the women were a major factor in defusing potentially dangerous situations. Few quarrels got so out of hand that serious injury and murder resulted and those were usually limited to quarrels between males. Nevertheless, there was also occasional male aggression aimed at females. We know of one case in the 1860s when a boy of 8 ordered a much older girl to bring him some water; when she did not move at once, the young master shot an arrow at her, causing injuries just above her eyebrow.

There was a well-developed sense of right and wrong among traditional Andamanese, but there was no mechanism beyond disapproval for punishing misdeeds. In a closely-knit society disapproval can be a weapon with a painful cut but it is not an effective one to prevent the sudden outbursts of fury and the loss of self-control among Andamanese males that was behind most serious violence. Whenever an individual had been hurt during a quarrel, it was left to the aggrieved party to take any revenge he thought fit. If the guilty man had the support of his own friends, he might well get away, literally, with murder. Personal attachment among Andamanese men was so strong that even the most blatantly guilty and all but the most unpopular could rally at least a few supporters around him.

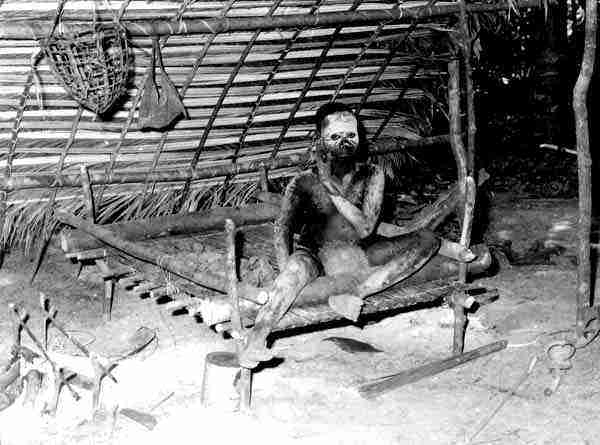

However, nobody could save a murderer from the traditionally prescribed cooling down period. The guilty man had to withdraw into the jungle for some weeks or months and was not allowed to feed himself or touch food with his own hands. His wife and some friends were allowed to live with him or visit him regularly to attend to his needs. There was a rigid taboo that the murderer could not touch a bow and arrow; he had to cover neck and upper lip with red clay paint and wear a plume of shredded wood in his belt before and aft as well as in his necklace at the back of his neck. If he broke any of these rules, the spirit of the person he had killed could make him sick. At the end of the period of withdrawal from society there had to be a purification ceremony during which his hands had to be rubbed in white and red clay and then washed. He could then return to his village and eat with his own hands again. For up to a year following his return the rehabilitated murderer had to wear plumes of shredded wood.

Given the explosive Andamanese temper and the special ritual associated with murderers, we must assume that murder was fairly common prior to 1858, although we do not know of any specific cases. After 1858 British justice moved energetically when a murder among Andamanese came to its attention. Sentences of flogging, hard labor in irons, imprisonment and in one case death by hanging were passed down. The Andamanese had no trouble understanding the principle of punishment and in many cases appreciated the preventive effect of a sentence swiftly matched to the crime. The prison sentences and other punishments handed down by the authorities were regarded by the Andamanese as an acceptable substitute for the traditional time a murderer had to spend in isolation.

Only once was a death sentence passed on an Andamanese man during the 19th century. The condemned man, Bia Lola, would without doubt be regarded as clinically insane today. It should be noted that the execution was widely accepted by the Andamanese with even the culprit's father agreeing that the sentence was justified. Bia Lola was the son of the headman of the Port Mouat sept of the Aka Bea tribe. In 1878 the young man had killed two children on the only grounds that they had disturbed his sleep. For this double murder he received two years of rigorous imprisonment but was pardoned and set free after serving 14 months. He killed again within seven weeks of his release: a young man, Riala, had accompanied Bia Lola's hunting party and had dared to eat a part of the pig that the leader had fancied for himself. Bia Lola did not immediately attack Riala but waited until early the next morning when he surprised his victim in his sleep, shooting two arrows into his stomach and killing him instantly. As there were no mitigating circumstances for this most unusual premeditated murder, Bia Lola was sentenced to death and died, trembling and pleading for his life, on the gallows at Port Blair on 19th May 1880 in the presence of M.V. Portman.

In another case of 1890, a small group of A-Pucikwar men and women were moving by canoe from one village to another in the early morning. The canoe carried , as usual, a small fire on its floor. An old woman found the morning chilly, raked the fire together and warmed herself over it. She did not notice that a newly made bow was near the fire and was getting charred. The bow's owner thought much of his new bow and was so enraged by the women's carelessness that he killed her with an arrow on the spot. The murder was reported to the British authorities who caught up with the man three months later and sentenced him to two years of rigorous imprisonment. The confined space within the boat must have been a contributing factor to the death of the woman who could not run away, yet many similar cases of enraged male adults shooting arrows at anybody near them, often injuring and killing innocent bystanders, are known.

Men and boys went armed most of the time so that quarrels involving them could quickly and easily escalate to murder. Knowing this, all but the hottest of hot-heads were careful not to provoke. Uninvolved bystanders tended to fade quickly and quietly into the jungle whenever they could see a serious quarrel developing.

The problems that the absence of a traditional system for punishing offenders caused the authorities as well as the use made of Aka Bea police auxiliaries are shown up well in the story of Kep and Chap:

On the 10th of July [1895] news was brought to me from the Middle [Great] Andaman that, several weeks before, a party of Andamanese from the North Andaman and Interview Island had been encamped on the west coast of the Middle Andaman. One of the men, named Chap, who had gone up to his country from the [Andamanese] Home at my house [at Port Blair] a short time before, asked the women to give him some firewood. They refused to do so, and he, after the manner of the Andamanese, flew into a violent passion, seized his bow and arrows, and fired off several at random, hitting no one. Having exhausted his stock of arrows he ran down to the canoes on the shore, took up a heavy spear from one, and returning with it stabbed Kep, the Chief of Interview Island, on the back of the right shoulder. The wound was a very severe one, and after lingering in great pain for several days Kep died from the effects of it. Only one man, named Bui, who had been formerly trained at Port Blair, made any attempt to seize Chap, and he took away his spear, but being much smaller than Chap, was unable to arrest him as he wished to do. The remainder of the Andamanese ran into the jungle and hid, making no attempt to arrest or punish Chap, nor, though they had bows and arrows with them, did they fire a single shot at him. The camp of Andamanese dispersed after the row, and Chap, after burning down my big Trepang-drying shed, which had taken nearly a month to erect, went into the interior of the North Andaman.

Kep was an elderly man, of mild and peaceable disposition, and had always been most friendly with us since I first made his acquaintance at Interview Island in January 1880. Chap, too, had always appeared to be well behaved, though somewhat stupid and deaf, and was for some months at my house. He was one of the Andamanese who accompanied me to Calcutta in February 1895, and was presented to His Excellency the Viceroy in Barrackpore Park.