The climate of their islands being what it is, traditional Andamanese went practically naked. The few items worn were not designed to protect but to decorate. The distinction between clothes and ornament does not exist among Andamanese. For protection from insects and the sun, much use was made of body painting with variously colored clay. Both clothing and body painting were and still are subject to such peculiar rules and traditions that an underlying religious significance must be assumed. We may remember the religious significance of the fibers used for the Onge female genital covering, the nakuinyage.

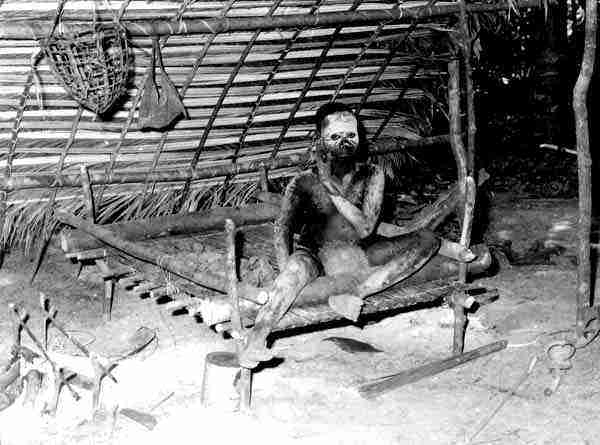

The men of the Greater Andamanese wore narrow belts or girdles of hibiscus fiber, sometimes decorated with other materials of different colors. The belts had a practical use since tools and weapons could be fastened to them, something that was especially useful during hunting expeditions when hands had to be kept free. Men also sometimes fastened leaves, cut into thin strips, to their belt, making the male dress look a little like the women's string skirts. Available photographs from the last decades of the 19th century and later show men and boys with traditional string skirts but also often with genital pouches and other types of covering made from non-native materials. These modern variations seem to have been insisted on by the early photographers. In the jungle, far from photographic equipment, the men went as their forefathers had done with nothing but the practical belt around the waist.

The women, especially the married ones, wore rather more about their persons even when out of camera range. They covered their genitals carefully and wore styles that in detail differed rather more from tribe to tribe than that of the men. The southern tribes wore bunches of leaves cut into strips and held by belts made of pandanus leaves. Among the northern tribes loose tassels made from strips of bark were the traditional fashion. The effect of both styles was that of short string-skirts. Most of these skirts covered only the front and not the back or had other gaps. Often tassels were added to the back which to the distant or casual observer could look like tails. Small duplicates of the style of skirt worn were sometimes added just above the knees to cover them and part of the lower legs.

Both men and women among the Greater Andamanese wore ornaments of sea shells, nuts or bone (including human bone) strung up on string long enough to be wound around the neck many times, sometimes with an added a strip of string netting for extra effect. Human skulls were carried around, not necessarily always of dead relatives but sometimes of strangers quite unknown to the carrier. It is a moot point whether a skull carried on a person's back should be regarded as a decoration or as a sign of respect for the dead. To the Great Andamanese it was both and yet another hint at the lost religious significance of much of Andamanese body decoration. On 19th century photographs we can see that small belts and strings of shell ornaments were also worn around the ankle and above the knees. Thus, from a rather limited number of clothing items, a considerable number of decorative combinations was available.

During dances, the Greater Andamanese of both sexes sometimes but not always wore additional items such as caps made of pandanus leaves with shells attached to them to make a rattling noise when dancing. A belt with similar shells was also worn attached to the wrist or knees.

Among the few surviving Great Andamanese the old-style clothes and decorations have not survived; in the 1990s they all wore Indian and western-style clothes as a matter of course.

Clothes and other decorations worn by members of the Onge-Jarawa group differed greatly from those of the Greater Andamanese but there were two significant similarities: both groups had a marked preference for the use of yellow in decorations and neither group used feathers or flowers to any extent although colorful birds and flowers would have been available in great abundance. These general Andamanese preferences are shared by the other Negrito groups, the Semang on the Malay peninsula and the Aeta in the Philippines, so that a reasonable case for their high antiquity can be made. Negrito reluctance to employ feathers and flowers is in marked contrast to the Papuans and the Australian aborigines who make exuberant use of the colorful material.

Among the Onge, ornaments of shells or nuts were not unknown but not common, as were decorative nettings. Necklaces were worn more by women than by men. Human skulls were not used but lower jawbones of humans decorated with fiber have been reported. The Onge wore belts made of bark around the waist as well as cords of cane strips woven together with thread, often with tassels of thread added to make a sort of skirt. Headbands of a somewhat similar design were also worn by men and women but bands around legs and ankles are unknown. The women wore and some still wear girdles of cane stripes with a large tassel in front, the characteristic nakuinyage. Another specialty of the Onge were strips of bark worn by the women over the shoulder and passing beneath the breasts. This last item resembles the strip of bark known to have been used by Great Andamanese, male and female, to carry infants around.

The Indians, as authoritarian and prudish in the 1950s as the British had been earlier, decreed that Onge women had to be decently clothed. The Onge women took to this but then exaggerated to the extent that they would not even bare an arm to visiting anthropologists, to the evident if inexplicable delight of their men-folk. The briefly fashionable prudery soon passed, on both the Indian and the Onge side. Only a few Onge women have reverted to the nakuinyage, most preferring an often topless version of the Indian sari or the western skirt. The men rarely go stark naked today, most wearing a genital pouch, a loin cloth or shorts of non-native material.

Jarawas, particularly the women, had long been thought to go almost entirely without clothes and other body decorations. Since the Indians have established closer contact with some Jarawa groups, it has become clear just how little reliable information was available on them - even about clothing which one would have thought was the one item most easily checked from afar. Most women and many of the men do wear clothes and other body ornaments. What is worn is fairly similar to items of the Onge wardrobe. Like the Onge but unlike the Great Andamanese, the Jarawas have not been seen to wear bands around their legs and ankles, nor do they use human bones and skulls. Contact with Jarawas has not been close enough so far to see whether they wear additional or special ornaments during their dances.

A particular form of elaborate headband is unique to the Jarawas. It consists of long bundles of yellow fiber that are fixed to the conventional headband and that hang down the wearer's back, looking for all the world like the long blond hair of top fashion models. Sometimes the fibers are worn long enough to reach the ground, more usually they reach only the small of the back. Men as well as women have been seen wearing these incongruous locks. Both sexes also occasionally use strings to enlarge their necklaces of shells. This is reminiscent of the decorative netting of the Onge but for the fact that the Jarawa strings are not netted.

Many Jarawa men go stark naked apart from a small necklace or a string around the waist or arms. Some men, however, have been seen wearing all sorts of other decorative items such as headbands and necklaces of fiber or shell as well as a rather odd piece of apparel, a sort of wide girdle, cuirass or corset made of bark fibers. This singular piece of male apparel does not seem to have any practical function; as a defense against arrow shot it is most unconvincing. However, if it is worn as tight as it usually is, the corset does make the wearer's chest much more prominent. The Jarawa corset may have had its origin in the belt worn by Onge men but it is much wider, reaching from the nipples to the navel. We do not know the reasons why some Jarawa men wear the corset while others do not. Does it signify status, a function or is it an individual whim?