Piraha tribe: The happiest folk in the world?

The amazing story of Daniel Everett

Joam Chomsky had his office next to his. When Daniel Everett was working on his linguistic work about the Piraha language, he still felt part of the scientific community at the MIT, the renowned Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Since then, many things have changed: Chomsky calls him (who is meanwhile teaching as a linguistic professor at the Illinois State University) a charlatan: Everett’s (first) wife divorced him after forty years of marriage, his kids partly took distance from him and his faith has left him irrevocably. In short: Everett’s life has taken a complete other turn than he could have imagined in the year 1977, when he hit the road to the Amazonas to meet the Piraha indigenous people. The Indian tribe of about 350 people has turned upside down all his basic beliefs, and today, the “New Yorker” as well as the “Spiegel” report about him: The former missionary has kicked off a linguistic debate that goes far beyond the expert groups.

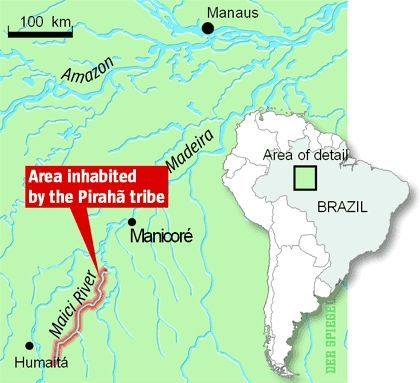

Why it came to this turmoil is being described by Everett in his book “Don’t sleep, there are snakes”. His story begins in a “broken home”, nearby the Mexican border. The father was an alcoholic, the stepmother committed suicide. At the age of 17 he found God, by 18 he had married the daughter of a missionary and with 26 he was with his five headed family on the way as a missionary. Everett had enjoyed a stern linguistic education and was enthroned with the task to learn the language of the Piraha tribe on the Amazonian river Maici and to deliver a translation of the bible - a tremendous project, as the language of the Piraha was unexplored and writings didn’t exist. Impressed by the fire of the proselyte, he moved with wife and children in a small hut near the river, three days travelling away from the so-called civilization. And he learned the hard way what it meant to live in the jungle, without health care, in brooding heat, without electricity and running water, threatened by snakes, wild cats, crocodiles and sometimes angry Pirahas. His wife and daughter almost died of malaria and the Pirahas watched unmoved. Their life expectation comprises about forty years, hunger and deadly diseases are normal. And Everett managed only curtly to escape from drunken, murderous Pirahas. Even so, his book is homage to the Maici-river people. Because they are happy people.

“Don’t sleep, there are snakes“ was one of the tips of the Piraha, they themselves sleep rarely more than four hours at a go. To be awake and be focussed in the present: That was the basic guideline of their (survival-) culture. They don’t have any creation myths, they don’t tell each other stories and a word for grandparents doesn’t exist. Instead there are suffixes who testify by eyewitnessing: To have seen something with one’s own eyes matters more than any other endorsement. Abstractions on the other hand are rare: numberwords for instance never occur, colourwords only in the form of comparisons (such as blood). There are no passive constructions, no subordinate clause, and no coordination. There are, in short, no so-called recursions, no embedment of a linguistic entity into another.

But recursions are the characteristic of what Chomsky considers to be the distinguishing feature of the human language, as the base of the universal grammar inherited in mankind and enabling it to acquire a language at all! But, according to Everett, they are absent in the Piraha as well as, he supposes, in other indigenous languages. The reason is, says Everett, the principle of immediacy of Experience, which is the basic principle that determines everything in the Piraha world, even the language. “The theory to which I have consecrated the main part of my scientific career, the imagination that grammar is a part of the human genome” considers Everett in the mean time as “completely wrong”. Language is nothing but an essential for surviving side product of human cognition, connected with the restrictions that govern life in a given culture. That is the reason why every linguistic investigation has to include an anthropological field study.

The heated debate about these issues is not yet closed; long dissertations about the topic have bee written from Chomsky adepts recently. Everett however goes on persisting with the affirmation that culture influences grammar in a considerable way. The Principle of Immediacy of Experience permeates the whole life of the Piraha. It leads to the fact, says Everett, that they would rather kill a sick baby than leaving Everett to coddle it up (because it is suffering and with the mark of death). It leads to the facts that adultery is not a sacrilege and violence is rare. And also, that they don’t have complicated social structures that goes beyond the grammar of Evidence (in which one says what one sees). The Pirahas live in the present and are, as anthropologists notice, the “happiest people on earth”. They are the one’s who laugh and smile the most of all the examined tribes, depressions and suicides don’t happen there. They don’t wish to possess more or to live differently. They don’t have future dreams and don’t complain about the past, western values are being (yet) rejected even if one like to borrow the boat with outboard engine.

How does one save a folk that doesn’t feel lost in the slightest? This question remained unanswered by Everett. In the contrary, it became for him more and more difficult to assert bulks that have never been seen by anybody, such as “Father in Heaven”? Everett translated the Marcus Gospel in Piraha language, but he found himself unable to accommodate it with the Principles of Immediacy and Eyewitnessing – and started himself to doubt. But only two decades after his fall from his faith he avowed himself to it and his marriage collapsed. If Daniel Everett is right with his analysis of the Piraha language, it is not going to be cleared out rapidly. No linguist in the whole world masters the language as good as he does. But the fact that the explorer explains to us the Piraha culture with the “Immediacy of Experience Principle”, that he neither builds on the stereotype of the “noble Savage” nor demonizes the “decadent West” makes him to be convincing. The Ex-missionary leaves the question of what happiness is for mankind open.