There are many caves in the islands but few are suitable for human occupation. Most have been inhabited by bats and birds rather than humans. Abris, or rock shelters, are known to have been used by hunting groups for brief rests but the Andamanese generally do not seem to have made much use of caves. The only cave that has been investigated archaeologically is Hava-Beel cave on

Given the islands' climate and heavy rainfall, combined with the apparent Andamanese reluctance to live in caves, an artificial roof over their heads must have been a necessity from early days. While Andamanese "architecture" varied in detail from tribe to tribe, all tribes had a number of fairly standardized structures ranging from the one-night shelter to more permanent individual village huts, to large permanent communal houses.

Temporary shelters were similar among all Andamanese groups. One type could be constructed in minutes with just a few large leaves stretched between the buttresses of a giant jungle tree. If this simplest of all constructions was not possible, a slightly more elaborate lean-to shelter was put up, consisting of a roof made of a few sticks and covered with large leaves, held up by two long poles in front and resting on the ground at the back. They did not have to last more than a night or two and could be built within minutes by an experienced hunting team.

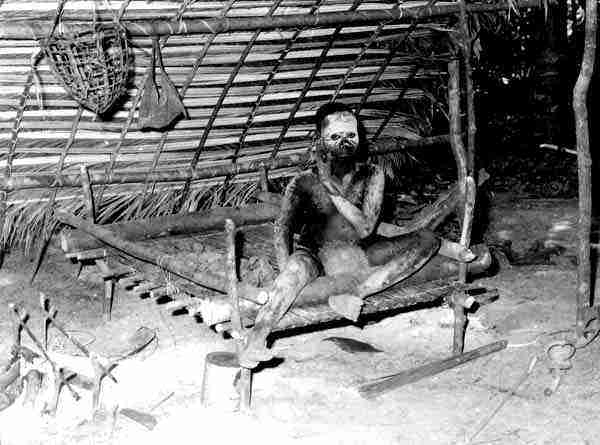

The more permanent huts of a village were a larger version of the temporary lean-to. They were put together more carefully and were far more durable. The roof did not rest directly on the ground at the back but instead was lifted a few feet by two short poles. The proportions between the higher front and the lower back varied between the various groups but the principle of construction was the same for all. The Great Andamanese, Jarawa and Sentineli thought and still think nothing of living and sleeping on the dry sandy ground or at most spreading a few leaves during the dry season. Only when the ground was really wet did the Great Andamanese construct low platforms on which to sleep. The Onge on the other hand did not like to sit or lay on the ground, dry or wet, and their huts always had and still have a raised floor a few feet above the ground and tied to the four pillars holding up the roof. The huts of all groups could last for months or years, depending on how much maintenance work was done on them by their owners. The owners were the nuclear families within a local group. They put them up and used them seasonally again and again whenever they were exploiting food resources nearby. For much of the year, however, the huts stood empty. Each family had a hut in several villages.

Huts were usually left open on sides and in front. Privacy was not a concern within the local groups. Sometimes screens would be made to cover the side exposed to the prevailing winds. Occasionally, if still more protection was needed from the elements two huts would be constructed so that they faced each other, with one roof projecting over the other. The two huts would not be connected structurally in any way; a gap would be left between the two roofs for the smoke to escape. Although such huts at first glance looked like one house, they would still in fact be two completely separate units with two different families as builder-owner-occupiers.

While the Jarawa-Onge tribes usually built permanent huts only for seasonal camps, the Great Andamanese, especially Aryoto groups, combined huts into main camp villages built according to certain traditional pattern. The precise form of a village need not always follow this pattern exactly but was flexibly adapted to local conditions and geography. Such a temporary village consisting of more than a dozen huts but with each containing no less than four or even five fire places has been seen on North Sentinel island recently. Since the Sentineli had, as usual, vanished into the jungle on the approach of the anthropological party, it could not be established just how many families or individuals lived in each hut. It is possible that each family kept more than one fire burning as a defense against insect pests.

While each local group maintained a string of seasonal camps, each also had one main camp where it spent the rainy season. It was the main camps and to a lesser extent the seasonal camps that built up what we know today as kitchen-midden. These piles of domestic refuse made up of stone chips, shards of broken pottery, bones and above all sea shells took centuries and millennia to accumulate. The highest known reach 5 m (16 ft). Clearly, village sites were moved only under the most dire circumstances, for example when a site was made untenable by the rising sea or when the source of fresh water dried up. Each local group had only its small territory with a correspondingly small number of suitable sites near its limited number of seasonal food producing areas. Local groups wandered endlessly on their annual rounds from camp to camp.

Main camps came in two forms. Some, but not all, Aryoto groups of the Great Andamanese built their main camps just like their seasonal villages and with the same internal structure. The only difference to the seasonal camps was that the huts would be built still more carefully and a little larger with additional amenities such as a raised floor and racks for storing food. A few of the Aryoto, all Eremtaga, Onge and Jarawa local groups built sizable communal houses. These are the largest and most complex structures known to the traditional Andamanese. It seems that all groups formerly built communal huts but that some Great Andamanese Aryoto groups had stopped using them before 1858.