It would be unfair - but not very - to say that the technology of the Andamanese could best be described by what it lacked. A list of technological marvels that they traditionally had to do without must at least include the following:

- animal skins and leather

- blowpipes

- clubs

- fish hooks

- pointed needles (thorns were not used)

- poison (including arrow poison; the only exception is the limited use of plant poison to stun fish)

- slingshot

- sails

- fire-making

Central to Andamanese life, but strangely peripheral to its religion, was the Fire. Individuals quickly sickened and even died without a physically and psychologically comforting fire burning nearby at night. In their humid climate - with a rather damp "dry season" and a truly wet "wet season," merely to keep a fire going was no mean achievement. Uniquely among living human groups, the Andamanese did not know how to kindle a new fire. Their inability, when first reported, was received so skeptically that one early observer was moved into an uncharacteristic outburst of fury:

Those eminent anthropologists who study savages from their firesides in England, and criticize and contemn the work of observers on the spot from their own lofty standpoint of ignorance (possibly because the results of those observers' work do not agree with their pre-conceived theories), are persuaded that the Andamanese must know how to make fire, or must have some word in their language showing that they formerly knew how to make fires. The fact however remains that the Andamanese do not know, and, judging from their language, never have known, how to make fire. They are very careful of their fires, always carrying smoldering logs with them when they travel either by sea or land, and so sheltering the stock log that even in the most inclement weather the fire does not become extinct. Should such a mishap however befall a village, the people would go to the next encampment and obtain fire from there. According to a Prometheus-resembling legend of theirs, fire was stolen from Heaven in the first instance and has never been allowed to become extinct since.

Controlled use of fire goes back at least 1.5 million years. The ability to make fire by rubbing sticks, with drills or by striking stones, has been traced back only to about 9000 years. Being rather difficult to prove archaeologically, it could be much older. It has been speculated that the Andamanese received their fire from an active volcano such as

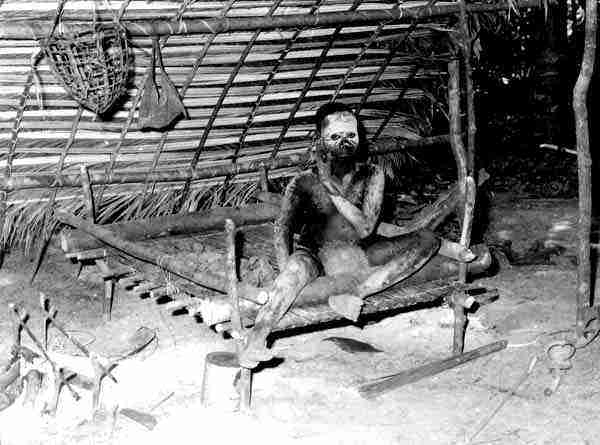

No reliable eyewitness accounts exist on how exactly the Andamanese moved fire when traveling: groups on the move did not welcome inquisitive outside visitors. Observers only saw freshly-settled groups with open fires already blazing. We know that migrating groups of all sizes routinely carried their fire with them, the glowing embers protected in clay pots and wrapped in large leaves. Additional smoldering logs were often deposited in protected dry places under tree roots as reserves and perhaps also for religious reasons. Among the Onge, some territorial boundaries were marked by small clearings in which one or two logs were kept smoldering. Woods were selected for the ability to smolder for long periods without going out or bursting into flame. Whenever a full fire had to be kindled, dried leaves were pressed against the smoldering log. One of the things that impressed the Andamanese most were the outsiders' matches.

For all its importance in daily Andamanese life, fire was invested with few spiritual properties:

Council fires, or fires burnt on special occasions, are not among their institutions; even the household fire is not held sacred, or regarded as symbolically of family ties, and no rites are connected with it; there are no superstitious beliefs in reference to its extinction or pollution, and it is never employed literally or figuratively as a means of purification from uncleanliness, blood, death, or moral guilt.

This description certainly oversimplifies since at least among Onge fire and smoke was traditionally used as protection against harmful spirits. Groups of Onge moving in single file through their forests are customarily led by a male or female leader (melame) who carried a smoldering log. The point of the exercise is to leave a protective smoke-screen above and behind the column. It may be noted here that it is the smoke, not the fire, that is credited with protective powers.

14.1 Pottery

Nearly as remarkable as the Andamanese inability to make fire was their ability to make pottery. The oldest known pottery goes back to the first farmers of the Middle East and

The southern Great Andamanese were the only group to ornament their pottery with simple decorations (see chapter 20). All other groups whose pottery we can trace into the past had plain, undecorated pots. Pots, unlike canoes, paddles, bows, skulls and other important items, do not ever seem to have been painted, even temporarily. The Onge produced pottery that was inferior to that of the Great Andamanese; it was never decorated in any way. The pots of northern Great Andaman usually had pointed and those of southern Great Andaman rounded bases. Since the Onge used both rounded and pointed forms in still more inferior quality, it has been suggested that the Onge had learnt the art of pottery from the Great Andamanese at an early stage. Little is known of Jarawa and nothing of Sentineli pottery but theirs does not seem significantly different from the known wares of the other groups.

Andamanese kitchenware never made any claims to aesthetic distinction. Pots were used for cooking, barter, the storage of foodstuffs and for carrying fire. They were articles to be used, not respected. There were no stories, legends or ritual surrounding them. Broken pots were thrown out as rubbish quite unceremoniously.

Clay of suitable quality occurs in many places in the archipelago with the possible exception of

Pots did not vary greatly in size: the bigger sorts were mostly for food storage in the main camps and were hardly ever moved, the smaller varieties were taken to the temporary camps and used while traveling. Medium-sized pots often received additional protection in the form of a woven basket that made them easier and safer to carry.

Irrespective of size, all pots were made of the same material and by the same method so that all were of the same rather low quality. Traditional pots were so brittle that their owners were only too happy to change to the sturdier vessels that the sea washed up on their beaches in ever-increasing numbers from the 19th century onwards or that could be acquired from outsiders. Such containers have replaced traditional pottery to the point when the Onge today cannot even describe an earthen pot, never having seen one.